Cultivating Resilient Food Systems: A Practical Guide to Forest Gardening in Aotearoa

This article is based on the presentation by Gary Marshall at the 2025 NZILA conference, Heretaunga Hastings, 22-23 May, 2025.

In uncertain times, changing how we grow our food offers a grounded, practical path to building resilience and may be one of the most impactful ways to drive lasting change. In this article, I want to discuss our food system and social change, highlight some of the ways these things fit together, and share some of the work that we have been doing at Aotearoa Permaculture Workshop (APW) and Resilio Studio to support the science, art and practice of forest gardening in Aotearoa.

Our Industrial Food System

Our food system is extremely complex. It is essential, and it permeates every aspect of our lives. As consumers, we meet the system in the supermarket, the dairy, and the farmers' market. As a grower, you will meet it in your garden and the field. If you take it to market, you will need to engage a wide variety of supporting industries - packaging, marketing, pickers and other staff, engineering and transportation, and perhaps manufacturers of fertilisers, pesticides, and fungicides. While our food system has helped to grow our global population to 8 billion people and counting, it is, at least here in the Global North, an industrial food system, profoundly embedded in our unsustainable modern market economy.

We are currently deeply dependent on this food system, and if it were to be disrupted in any significant way, we would suffer malnutrition, likely slip into poverty, and many of us could even starve. Our food system has become “too big to fail”. And yet, this system is directly and indirectly responsible for a wide range of ecological, cultural, social and economic ills that are slowly impacting our ability to grow food. We are caught in a bind; we are reliant on a food system that is undermining its own integrity. However, despite industrial agriculture utilising over 75% of the world’s agricultural resources, it provides only 30% of our food. The other 70% comes from local growers working on small landholdings and distributing food through informal markets. This may come as a surprise to some, but globally, the world still feeds itself mainly outside the industrial food chain. This observation highlights the fact that if we can see beyond our assumptions and dependencies, we can begin to recognise that there are effective alternatives to our existing industrial food system.

Theories of Change: Food Growing and Social Transformation

In our work, we use theories of change and frameworks for social innovation when designing in the social domain. The model I use here, which comes from social futurist Sara Robinson, highlights three broad strategies - Revolt, Reform and (Re)build.

Revolt is about direct action. It is about challenging and disrupting the existing power structures, particularly governments and corporations that are seen as the cause of our environmental and social challenges. In the early 2000s, New Zealand witnessed mass protests against the introduction of genetically modified organisms into Aotearoa. Tens of thousands marched, thousands more engaged in direct action, halting trials, and forcing moratoriums. While there were victories, they remain incomplete and potentially temporary as the merger of biotech and our food system continues unabated.

While I support many of the same causes that inspire this kind of social action, revolutions often don’t unfold as intended. More organised forces can quickly overtake those who initiate them, and without long-term structural changes to our political economy, revolution alone is rarely enough. Unlike gradual, evolutionary change, revolutions bypass the trial-and-error process that allows successful ideas to take root and spread. A recent example is Sri Lanka’s abrupt, top-down shift to organic agriculture; the rate of change didn’t allow for the incremental testing and refinement necessary for lasting systemic change, ultimately causing significant disruptions to food production and national stability.

Reform is concerned with the incremental improvement of our existing social structures. If you are working toward social change in a modern market economy, more often than not, you will be attempting to reform the system from within. As a landscape architect and a business owner, this is where our core business generally lies.

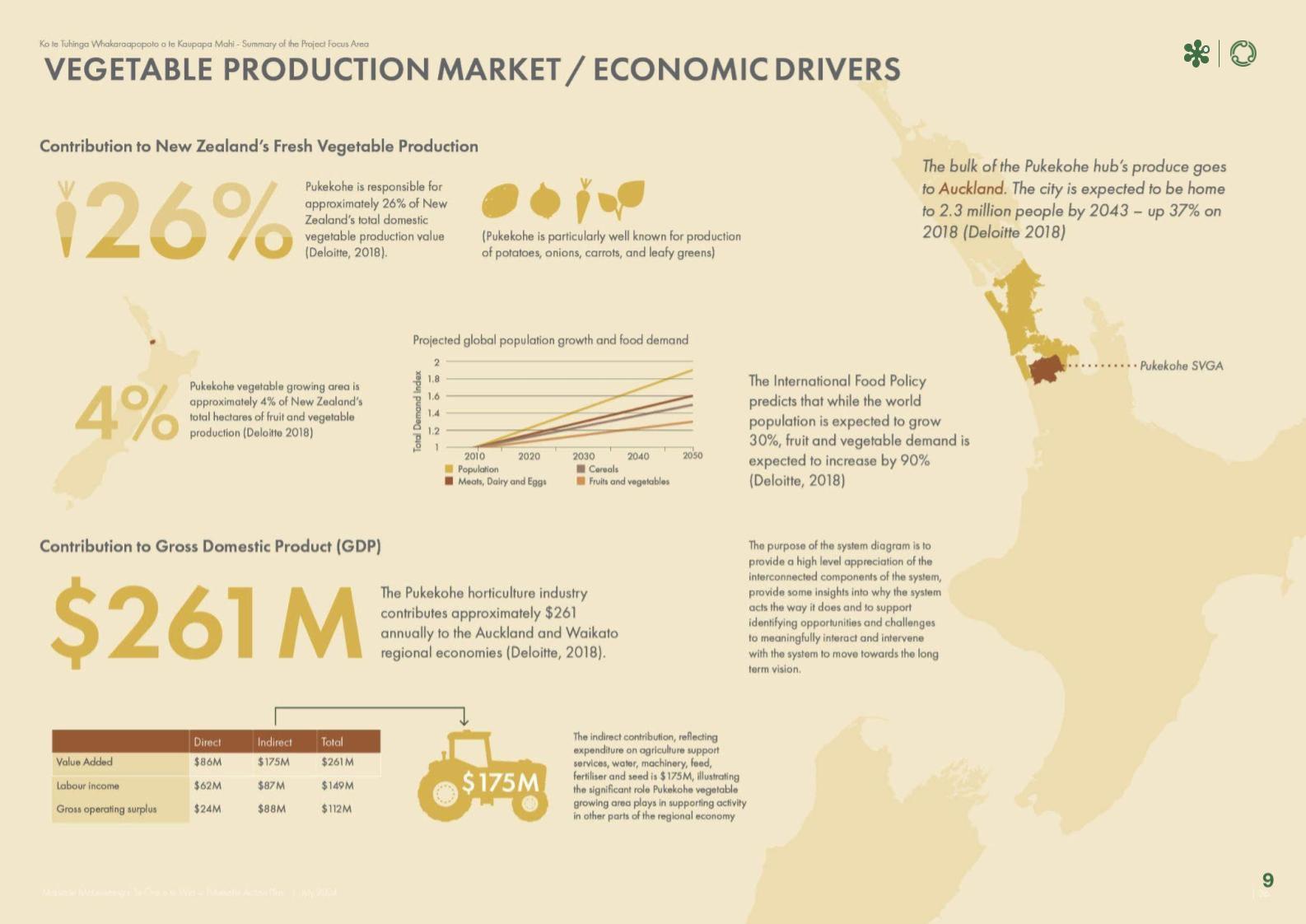

Mahia Te Maheretanga: Te Ora O Te Wai - The Pukekohe Action Plan highlights some of the challenges and limitations of incremental reform. For this project, we worked as part of a team tasked with helping Crown, local councils, mana whenua, and commercial vegetable growers collaborate to address water quality degradation in the Pukekohe area. Pukekohe’s groundwater nitrate levels are now 80 times above safe drinking limits. Even with all current best practices implemented, models suggest nitrate levels will remain 40 times above safety limits. The situation is exacerbated by the fact that the aquifers could take as long as 100 years to recharge, meaning that the efficacy of physical interventions will be unknown across meaningful time frames.

At the same time, the affordability of fresh vegetables is strained. Changes in farm practices incur additional costs for the grower, which are passed on to the consumer. However, the cost of living in Aotearoa is already a challenge for a growing number of people, many of whom cannot afford fresh fruit and vegetables. This downward pressure on prices also makes it difficult for farmers to employ workers at a livable wage. Our food system is tightly strung with strong interdependencies. It self-organises around the principle of competition.

To paraphrase David Fleming, author of Lean Logic: A Dictionary for the Future and How to Survive - “growers must produce food at a price that is at least as low as that of other growers, growers who are not competitive have to raise their game or cease to exist… [this] taughtly strung system leaves little room for the freedom of its parts.”

It was not our role to propose solutions through the development of the Pukekohe Action Plan - we were there to listen and facilitate dialogue between the different parties. Still, we did get the opportunity to share findings from an extensive literature review of promising local and international initiatives and growing systems backed up with empirical data and demonstrated, real-world results. Many of these examples extol the virtues of small-scale regenerative agriculture, closed-loop nutrient cycling, local economic development and food sovereignty. Yet tellingly, any food growing systems that strayed too far from Business as Usual were excluded from the Action Plan.

I don’t highlight these challenges to blame anyone; the Pukekohe Special Vegetable Area provides Aotearoa with 26% of its fresh vegetables. I share these insights to highlight that so long as we buy vegetables from supermarkets, greengrocers, cafes and restaurants, as I do, we are all embedded in the intractable complexity of our industrial food system. be explicit about the inability for actors in a taut system to make any significant change - as unsuccessful innovations equals failure that growers cannot recover from in a market economy. If systemic change is required, which I believe it is, we need approaches that move beyond incremental responses that aren’t bound by the constraints of the existing market economy. Robinson’s third theory of change - Building and rebuilding strategies are less concerned with taking on the existing system head-on and more concerned with creating parallel structures and resilient alternatives that sit outside the existing market economy.

David Holmgren, co-originator of the permaculture concept, reminds us that self-reliance through food production is a political action. Every herb grown in a garden, every crop given to a neighbour and every barter made at a local market loosens the strings of our tightly bound food system a little and opens up space for new possibilities. To grow food locally — in gardens, in cooperatives, in communities — is to build and rebuild local food economies based on the principles of reciprocity, where people act in each other’s interests, transactions are based on trust and often informal, functioning without the use of money.

The aim isn’t to replace the supermarket overnight but to quietly weave a resilient, parallel economy underneath the visible one that either makes the existing model redundant or supplants it when it no longer proves helpful. While not facilitating change at the speed and scale that is arguably necessary, strategies that seek to build and rebuild parallel structures hold the potential for lasting systemic change in a way that incremental reform will never achieve. Forest gardening represents one of a handful of regenerative land use practices available to us here in Aotearoa that can be widely developed in parallel to our industrial food system, by anyone with access to land, basic growing skills, and an interest, knowledge and passion for growing.

Forest Gardening in Aotearoa

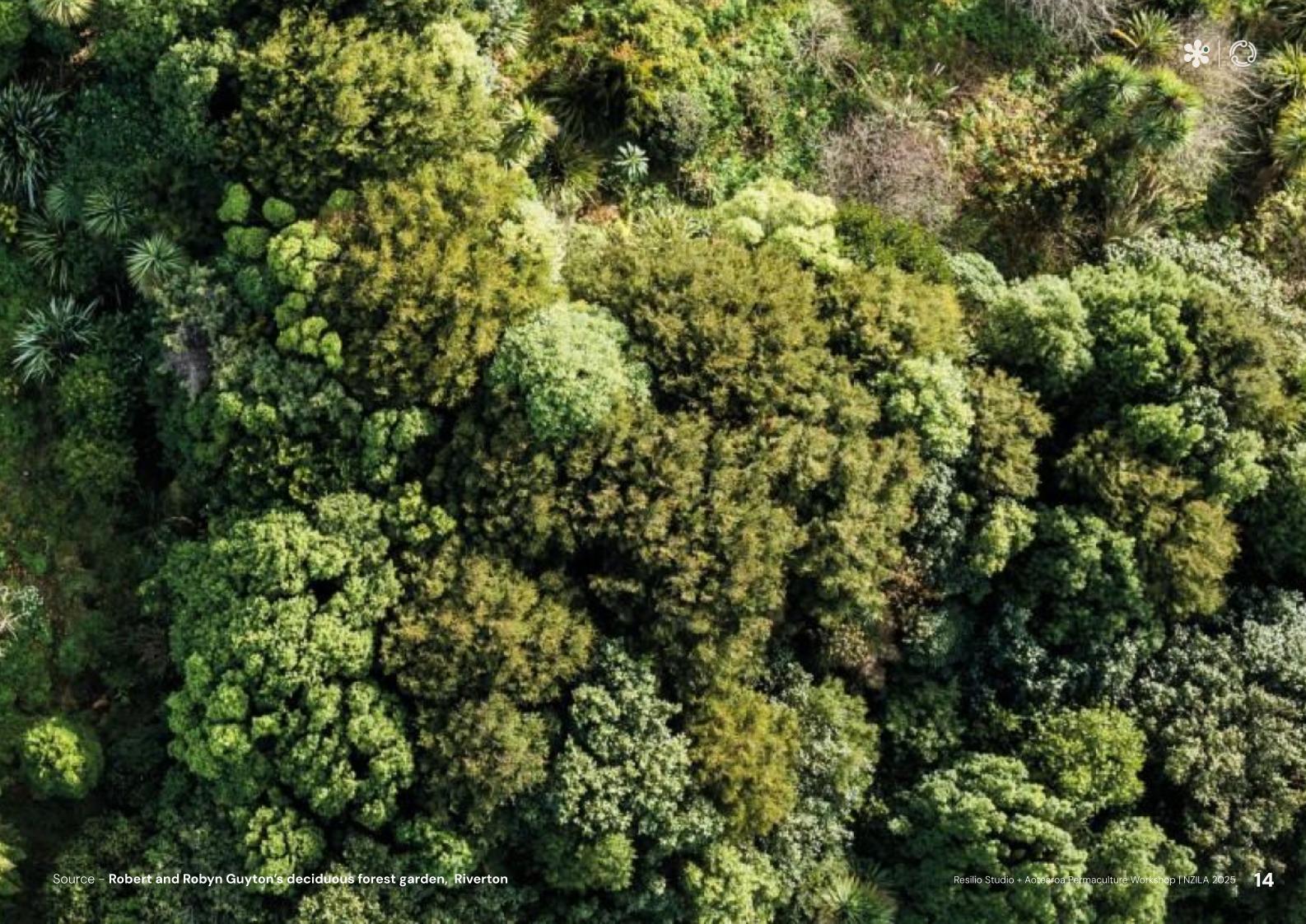

Forest gardening has been practised by indigenous people around the world for millennia. And while there is increasing interest in forest gardening, the available resources tend to be either too general or specific to locations and climates that are not necessarily relevant to us here in Aotearoa. A good example of this is revealed through a short internet search - type in the keywords “forest garden” or “food forest”. Look at any of the top ten videos of this search, and you will likely hear someone sharing how a forest has seven layers - ground cover, canopy, emergent layers, etc. Well, yes and no. Yes, forests in tropical climates have seven, even nine layers; however, here in Aotearoa, our temperate, broadleaf conifer forests have five layers, and our beech forests have between two and four. If forest gardening is going to play a role in building a parallel food system here, we think there is value in exploring forest gardening that is better suited to the ecosystems of Aotearoa. Over the last decade, my colleagues and I at APW and Resilio Studio have been researching forest gardening to help fill this niche.

For the last 10,000 or so years and for much of her 65 million-year history as a collection of islands, Aotearoa has been and still could be a forested landscape. Because much of Aotearoa is naturally a forested landscape with a relatively mild climate, it is particularly well-suited to forest gardening.

A forest garden is a garden designed and tended with the layers and complexity of a forest in mind. While not as productive as commercially grown crops that focus on single yields, a forest garden offers similar benefits across a greater diversity of harvests - food, fibre, fuel and medicine - while regenerating ecosystems, providing multiple ecosystem functions, and building resilience. This is true of most places, particularly in areas of land less suitable to intensive cropping.

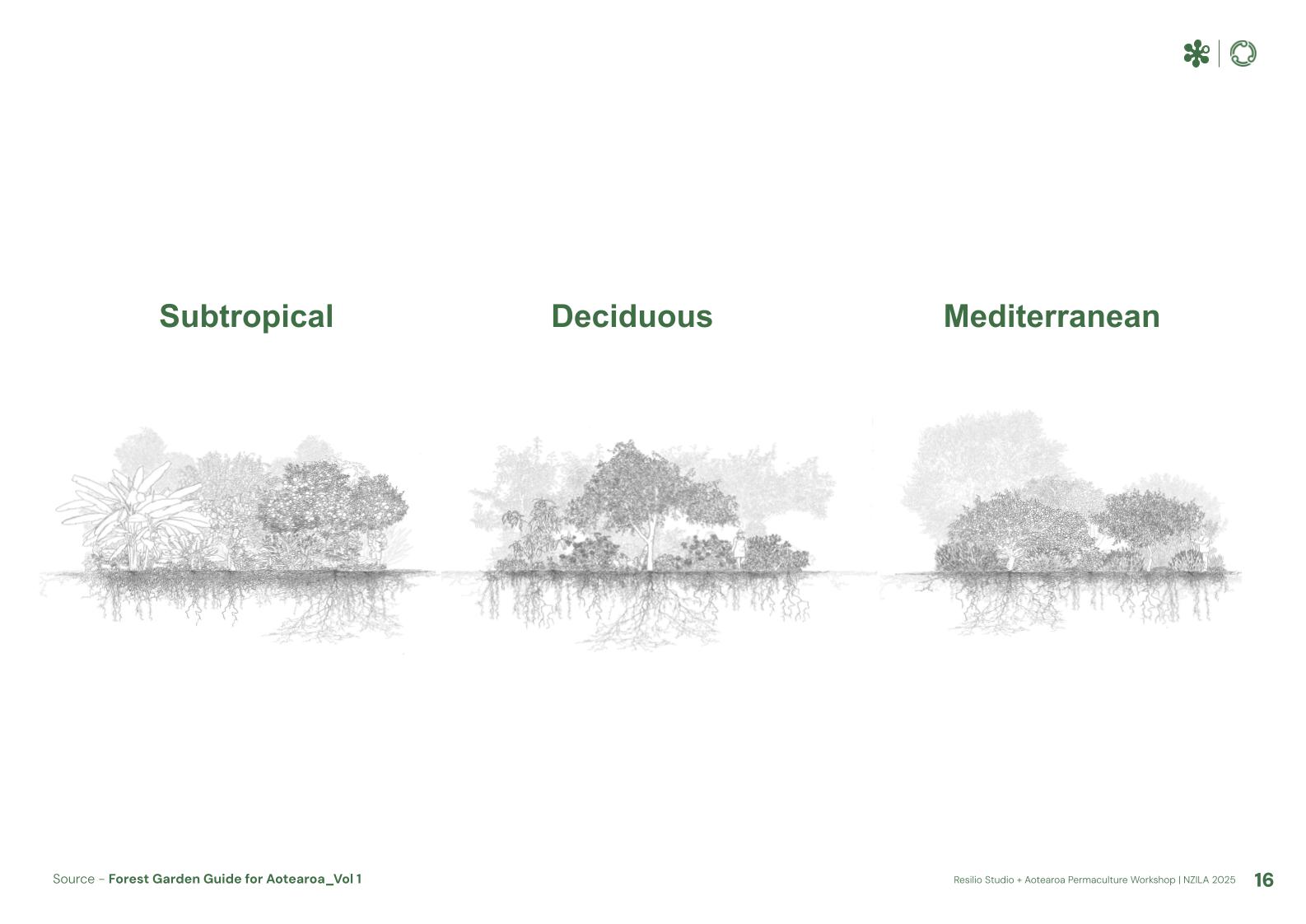

When we think about a forest garden as a biodiverse, multi-layered orchard, it helps us to think about different types of forest gardens suited to different climates in the same way that broadleaf conifer forests or beech forests reflect underlying landscape patterns. In this sense, there are four broad types of forest gardens - tropical, subtropical, Mediterranean and deciduous, each responding to different climatic and geographic conditions. Most places around the world are well suited to one or two types of forest garden - the cold winters and mild summers in the northern latitudes of the northern hemisphere support deciduous forest gardens but little else, while the warm summers, mild winters, and limited rainfall of the Mediterranean are well suited to, well Mediterranean forest gardens. Unlike many countries, Aotearoa can support three distinct types of forest gardens: subtropical, Mediterranean, and deciduous.

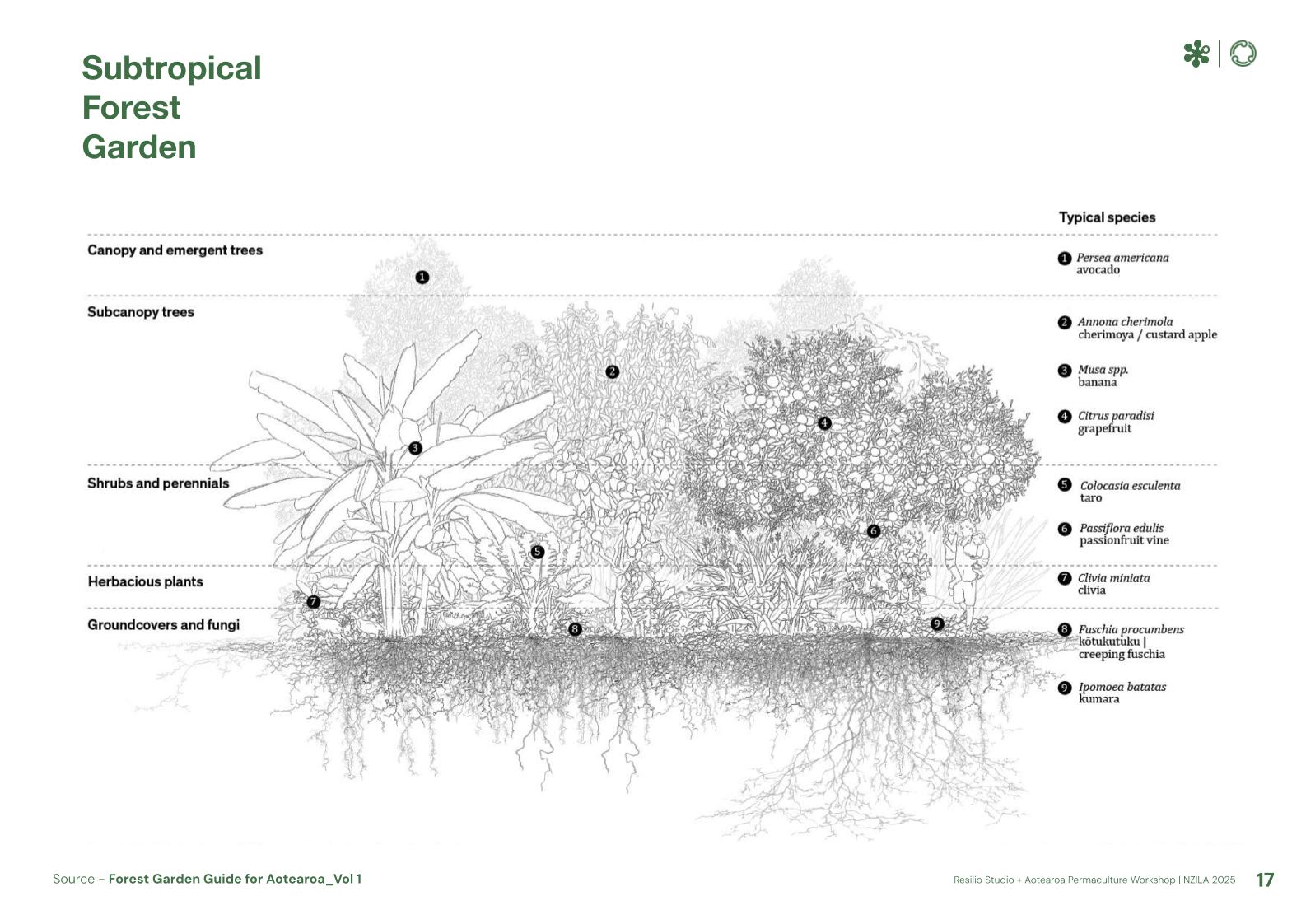

Subtropical Forest Gardens

The subtropical climate has warm, humid summers and cool, mild winters. Subtropical forests have dense canopies with five layers, similar to the broadleaf conifer forests of Aotearoa. Soils are typically rich and loamy. Species might include avocado and inga bean canopy trees; a sub-canopy layer of banana palms, papaya, and tamarillo; hibiscus shrub layers and ground covers of nertera. In Aotearoa, areas suitable for subtropical forest gardening include Te Tai Tokerau/Northland; Tāmaki Makaurau/Auckland and microclimates throughout the Whakatū/Nelson rohe and Tauranga Moana/ Bay of Plenty.

Syntropic agroforestry is a form of forest gardening well suited to fast-growing tropical and subtropical climates and species that emphasises natural forest succession, utilising precise pruning and planting timelines to accelerate ecosystem regeneration.

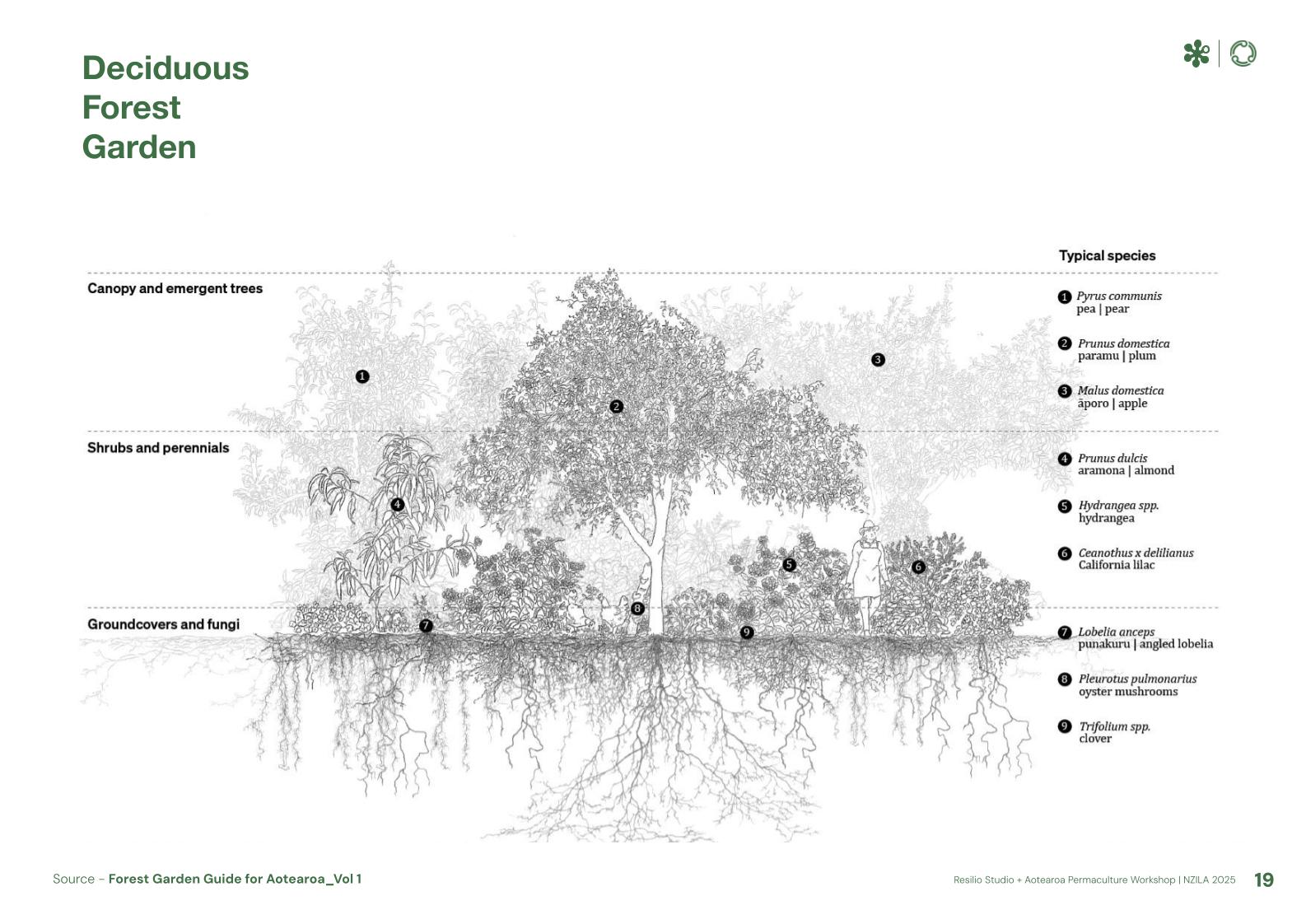

Deciduous Forest Gardens

The deciduous climate has varying temperatures with four distinct seasons. Deciduous forests have open canopies with 3 - 4 layers, similar to the beech forests of Aotearoa. Soils are typically fertile and hold nutrients during dormant seasons. Species could include emergent pear, plum, and persimmon canopy trees, blueberry and echinacea shrub layers, and chamomile and strawberry ground covers. In Aotearoa, areas suitable for deciduous forest gardening include the Waikato basin, the Taranaki rohe, much of lower Te Ika-a-Māui / North Island, and food-growing areas of Te Wai Pounamu / South Island.

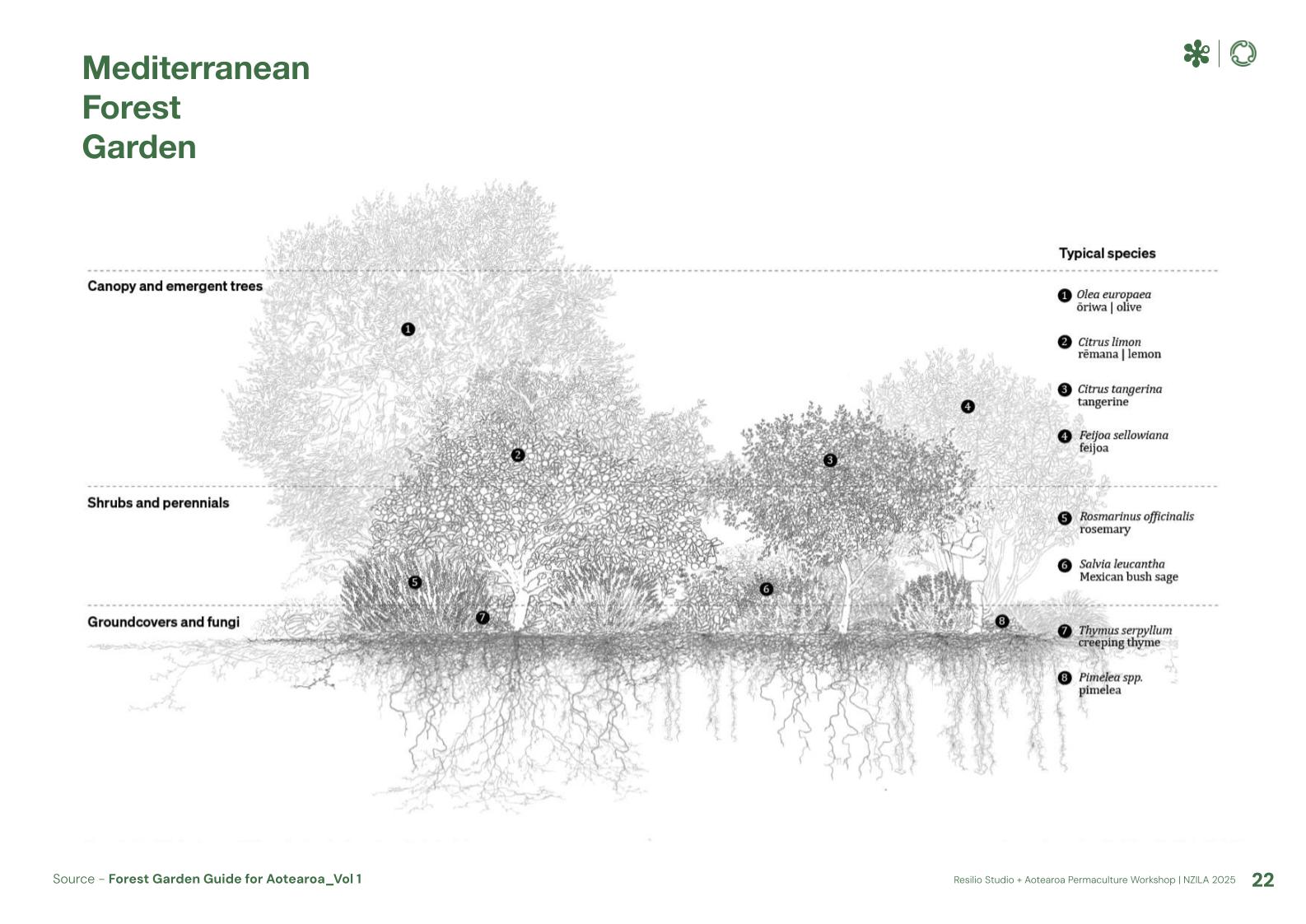

Mediterranean Forest Gardens

The Mediterranean climate has hot, dry summers and cool, damp winters. The trees in Mediterranean forests are widely spaced and have open canopies with three layers. Trees require full sun and good air circulation to minimise fungal diseases. Soils are typically free-draining. Species might include olive, fig, and pomegranate canopy trees; rosemary, lavender, and sage shrub layers, with ground covers of thyme and oregano. In Aotearoa, areas suitable for Mediterranean forest gardening include the east coast of Te Ika-a-Māui / North Island and Te Wai Pounamu / South Island. More broadly across Aotearoa, climate models suggest that we will experience warmer, drier climates in the coming decades and centuries, meaning that we can anticipate larger areas of Aotearoa being suited to Mediterranean forest gardens.

Forest Garden Guide for Aotearoa

For the last 15 years, we have been researching and practising forest gardening around the upper North Island. Based on this work and experience, we have developed a guide to provide practical advice on the science, art and practice of forest gardening in Aotearoa. We have done our best to make it accessible and replicable to anyone interested in forest gardening. We hope this will contribute to a diverse and growing community of forest gardeners who develop and refine ecologically responsive and regenerative food systems in Aotearoa. This is what David Holmgren has to say about it:

“The forest garden concept has been central to permaculture horticulture experimentation around the world over many decades. This design-focused guide distils lessons learnt and models for the next generation of forest gardens in Aotearoa.” David Holmgren, 2025.

We have just released the first of four volumes that guide forest gardening in Aotearoa. Volume 1 - An Introduction to Forest Gardening in Aotearoa gives readers a general introduction to designing, establishing and maintaining forest gardens in Aotearoa. The following three volumes, which we will release in 2026, will provide plant lists for three different types of forest gardens suited to Aotearoa.

We will update these guides as we learn more and receive feedback from a network of Aotearoa-based forest gardeners who are testing and refining their practices through trial and error. If you have feedback or reflections on the usefulness of this guide and the information it contains, we would love to hear from you at info@apw.org.nz.

To learn more about forest gardening in Aotearoa and access our free guide, visit APW's website.

Aotearoa Permaculture Workshop - https://aotearoapermacultureworkshop.org.nz/

Forest Garden Guide for Aotearoa - https://foodforest.apw.org.nz/forestgardenguidevolume1

For guidance and support in your forest garden design, contact us at Resilio Studio.

Happy forest gardening, ngā mihi, Gary, Resilio Studio and the APW team.